The Teacher Who Made Me Political

In Memory of Mahmoud Behkish

By Reza Yazdi

In the turbulent years before Iran’s 1979 Revolution, many young teachers and students found themselves caught between idealism and repression. Mahmoud Behkish was one of them — a physics student turned teacher, a man who brought literature and critical thought into the classroom, and who would later be executed in Evin Prison during the 1988 mass killings of political prisoners. The author, once his student, remembers the man who first taught him to think — and to resist.

From the moment he walked into the classroom, I knew that he was different. He was young — barely twenty-one — wearing a brown suit that wasn’t quite new, and shoes that looked worn from long days of walking. His beard was rough, unshaven. His face was serious, almost stern, but his eyes were kind — deep, searching, alive.

He didn’t bark orders like other teachers. He didn’t shout “Stand up!” or demand silence. In those days, it was a ritual: the class monitor would cry “Stand up!” when the teacher entered, and only when the teacher said “Sit down!” could we return to our seats. But when this man arrived, no one stood. Maybe the monitor thought he was another student — one of those older boys who had failed a few grades and looked out of place in a high school classroom.

It was early autumn in Mashhad. The air still smelled of summer — dry, warm, with a faint dust rising from the unpaved streets. We were tanned from months of sunlight and football games in the alleys. The new teacher looked as though he had spent the summer just like us — running barefoot after a ball, under the harsh sun.

He picked up a piece of chalk, turned to the blackboard, and wrote in clear handwriting:

“Mahmoud Behkish — Physics Student.”

Then he turned to face us and said calmly,

“My name is Mahmoud Behkish. I’m a physics student. I’ll be your physics teacher this year.”

That’s how it began.

But Mahmoud wasn’t just a teacher of physics. He was something more — a teacher of ideas. After a few classes, he told us that each session would be divided in two: one hour for physics, and one hour for reading. That day he opened a small book — The Little Black Fish by Samad Behrangi — and began to read aloud.

When he reached the line,

“Death can come easily to me, but as long as I am alive, I must not go to meet it. Yet if one day I meet death — and I will — it does not matter. What matters is whether my life or my death has made any difference to others,”

he paused. He read it again. And again. His eyes moved across the room, resting on each of us.

At thirteen or fourteen, I didn’t truly understand death. But I remember the silence that followed those words — the gravity in his voice, as though he were reading his own fate. Later, I would realize that while Samad Behrangi wrote that one should not go to meet death, Mahmoud had already chosen to. He wanted his life — and his death — to matter.

From that day on, every lesson was a window opening onto another world. He brought us The Exception and the Rule and He Who Said Yes and He Who Said No by Bertolt Brecht. He read Twenty-Four Hours of Wakefulness, another story by Behrangi, about children who worked in the streets and dreamed of a rifle behind a toy-shop window. When Mahmoud repeated the final line — “I wish that rifle behind the window were mine” — it felt as if he were speaking for himself.

We didn’t know it then, but he was already under surveillance. One day, in the middle of class, the school principal, Mr. Qavami, entered and asked him to step outside. Mahmoud walked out, holding a copy of Behrangi’s On Education, and never came back.

Rumors flew: that the secret police had taken him, that someone had reported him. Weeks later, I found out that he’d been arrested on December 7, Student Day — and sentenced to a year in prison.

Years passed. When the revolution came, Mahmoud was released from Evin Prison. He had long rejected armed struggle and joined a leftist organization called Razmandegan — “The Fighters.” He married, had a child, and tried to build a better society. But the new regime turned on its own revolutionaries. Soon, the prisons filled again — this time with those who had helped topple the Shah.

When I was imprisoned in Vakilabad Prison in Mashhad, Mahmoud was once more behind bars in Evin. I didn’t know then that he would never leave alive.

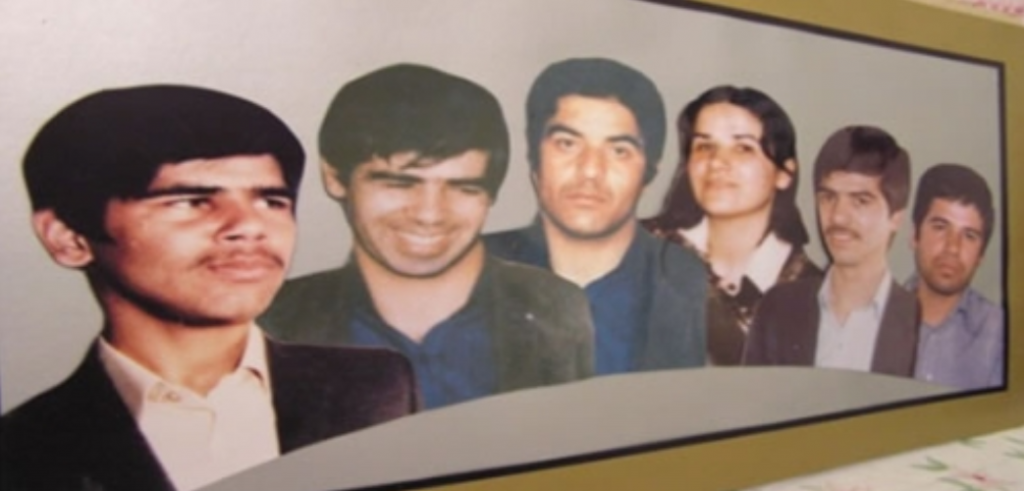

In the summer of 1988, during the mass executions of political prisoners across Iran, Mahmoud Behkish was executed. His brother Ali — the youngest — was executed too. His sister Zahra was tortured to death. Mohammad, the brother I had met once outside their home, was killed in 1981 in an armed clash. Esfandiar, Zahra’s husband, was killed the same year. Another brother, Mohsen, had been executed earlier.

The Behkish family lost five children and a son-in-law in less than a decade.

When I was finally released after six years in prison, I went to visit them in Karaj. Their mother opened the door — kind, dignified, her face marked by unimaginable loss. On the wall above the room hung framed photographs of all her children — each one gone.

Her husband sat in silence, rolling a string of prayer beads through his fingers. He looked up at Mahmoud’s picture. I did too. His eyes — those same eyes that once held a classroom of restless boys — were still fixed on me.

I don’t know if it was Mahmoud or the Little Black Fish who whispered in that moment,

“If one day I meet death — and I will — it doesn’t matter. What matters is whether my life or my death has made any difference to others.”

Mahmoud’s life, and his death, did make a difference in my life forever.

His memory will always remain with me.

August 5, 2010 – Mashhad